Acclaimed South Africa born author and academic, Zoë Wicomb was remembered during the Nobel in Africa Nobel Symposium in Literature held at STIAS recently.

Wicomb, a STIAS Fellow who was in residence during the first semester of 2016, passed away last month, a few weeks before she would have been part of the Symposium.

Her fellow Fellows and colleagues paid tribute to her life and work, saying it was difficult to come to terms with her death.

African literature scholar, Grace A Musila first met Wicomb at a conference organized by another STIAS Fellow, Maria Olaussen in Sweden; then subsequently spent time with her at STIAS when hers and Wicomb’s fellowship stints overlapped in 2016. “We remained in touch since then. I was looking forward to seeing her again in early November 2025 – coincidentally, at STIAS, at the Nobel Symposium, co-convened by Maria Olaussen. Maybe we would have shared a glass of Kaapse Vonkel,” Musila said.

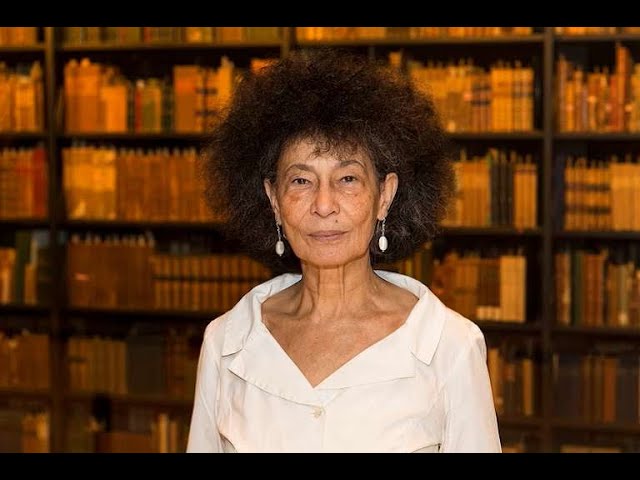

“I am having great difficulty thinking about Zoë as no longer with us. She is one of the most vivacious people I know. Her quick, straight-backed walk. Her sharp eyes. Her witty mind. Her voice that always reminded me of the clean clink of crystal glassware (she mustn’t hear this – she will be unimpressed by such inelegant phrasing and will tell me as much). Her stylish clothes. Her gorgeous hair whose fullness I have always envied. Her laughter. Everything about her spelt vitality and presence. It is counter-intuitive to think of Zoë Wicomb not being here,” said Musila.

“But then again, the paradox of her being gone is consistent with her other paradoxes. She often said how difficult, how torturous, writing was to her. Hard to believe, for those who relished the seemingly effortless flow of her writing, every word so evocative,” Musila said.

Wicomb was born to a Scottish father, Robert Wicomb and a Griqua mother, Rachel Le Fleur in 1948. She studied for a BA at the then University College of the Western Cape. She moved to London in 1970 where she studied for a second BA at the University of Reading. After graduating, she started teaching in Nottingham. She obtained a master’s degree from the University of Strathclyde in 1989, after which she returned to South Africa and taught at the University of the Western Cape for three years before returning to Glasgow. She spent most of her adult life in Scotland, where she taught at the University of Strathclyde until retirement. Her first book, You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town was published in 1987. She went on to publish several other books including Colours of a New Day (1990), David’s Story (2000), October (2015) and Still Life (2020), which she started writing during her STIAS residency in 2016.

Iso Lomso Fellow, and literature scholar, Wamuwi Mbao described Wicomb as a towering figure in the literary world. “Her writing – in all its varied genres - presented a rich and vital argument for the necessity of unspooling the tangled fictions that make up life in South Africa”, said Mbao.

“I encountered her work for the first time as an undergraduate reading You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town, David’s Story and Playing in the Light, deeply readable works of fiction whose creative landscape is the emotional, fraught way we encounter the past from our position in the present. Her work from the earliest to the last has been marked by an insistence on avoiding simplifications of complexity around race, class, gender and identity, and it feels so very evocative and pertinent today,” he said.

Symposium co-convener, Tina Steiner said she knew Wicomb from a few encounters at conferences and a friend’s wedding. “But it is through her writing, having first read her work as an undergraduate student at UCT, that I feel I knew her a little. Her last novel, Still Life (2020) remains vivid in my mind and feels like a particular gift: a work whose wit and wry humour deepen rather than undercut its political seriousness,” Steiner said.

“Reading it, I would find myself chuckling aloud at some of the characters’ antics. There is something liberating in the way she allows irony, tenderness, and scepticism to coexist. At once subtle and incisive, her wit feels like a form of care,” Steiner observed.

“When I bumped into her at the Baxter Theatre at the beginning of this year, I introduced myself as one of the co-convenors of the Nobel in Africa Symposium – we had corresponded a little about that – and walked away from the slightly awkward encounter cross with myself for not telling her how much I had enjoyed reading Still Life. I later dropped her an email to apologise for the awkwardness and to tell her what I thought of her novel. This was her response, which I believe is characteristic of her:

“Three cheers for awkwardness ––better after all than being socially glib.

As you will know, Tina, there is so much terror involved in both writing and letting it loose into the world, that nice words about one's work mean a lot.”

“I admire not only her brilliance but the quirky grace with which she held both intellect and vulnerability in balance,” Steiner said.

Day 2 of the Symposium started with a panel dedicated to Wicomb’s life. A recording of the session is included below.